Researchers call for a significant cut in antibiotic prescriptions

Scientists studying the effect of antibiotic prescriptions on the environment say there would need to be an 80 per cent fall in antibiotics entering the River Thames to avoid the development of antibiotic-resistant ‘superbugs’.

Researchers from the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (CEH) modelled the effects of the development and spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in a river. They found that, across three-quarters of the River Thames, the antibiotics present were high enough for antibiotic-resistant bacteria to develop.

The study comes after England’s chief medical officer Professor Dame Sally Davies warned that antibiotic resistance could kill humans “before climate change does.”

Results are published in the journal PLOS ONE.

“Rivers are a ‘reservoir’ for antibiotic-resistant bacteria which can quickly spread to people via water, soil, air, food and animals,” said Dr Andrew Singer of the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. “Our beaches offer a similar risk. It has been shown that surfers are four times more likely to carry drug-resistant bacteria than non-surfers.”

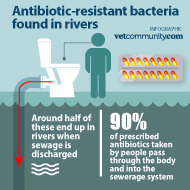

Ninety per cent of antibiotics taken by people enter the sewage system after passing through the body, with around half ending up in rivers when the sewage is discharged.

“The release of drugs and bugs into our rivers increases the likelihood of antibiotic-resistant genes being shared, either through mutation or ‘bacterial sex’,” explains Dr Singer.

“This is the first step towards the development of superbugs as the drugs used to fight them will no longer work. Environmental pollution from drugs and bugs is a serious problem that we need to find solutions to.”

Researchers say there are several possible solutions to cut the number of antibiotics that enter our rivers. These include reducing inappropriate prescriptions, taking preventative action so fewer medicines are needed in the first place and increased investment in the research and development of new wastewater treatment processes.

The Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) is inviting applications from veterinary students to attend a one-week extramural studies (EMS) placement in July 2026.

The Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) is inviting applications from veterinary students to attend a one-week extramural studies (EMS) placement in July 2026.