Device may allow disease eradication programs to resume

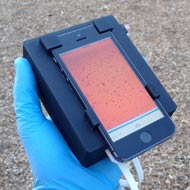

A smartphone has been used to detect the 'wriggling' motion of parasites in the blood. The rapid test could allow suspended disease eradication programmes in Central Africa to resume.

Attempts to eliminate two parasitic diseases - onchocerciasis (or river blindness) and lymphatic filariasis (LF) - have been put on hold as the anti-parasitic treatment, Ivermectin (IVM), can cause serious adverse effects, even death, in patients who also have high levels of the Loa loa parasite.

Small trials of the CellScope system in Cameroon have proved successful, scientists report in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The device works by filming a pinprick of blood and analysing movement to predict the number of L. loa parasites present in the sample. This allows healthcare workers to decide whether the patient can be safely treated with IVM.

These findings could facilitate a proposal to 'test and (not) treat)', whereby patients are screened prior to treatment with IVM, and those with high levels of L. loa microfilariae are excluded from the mass drug administration program.

For this proposal to be put into place, a rapid and inexpensive test is needed that can be used at point of care.

Current manual counts require trained healthcare workers and laboratory equipment, however, the CellScope system can provide results in minutes and workers do not need substantial training in order to use it.

L. loa is highly endemic in Central Africa. Diseases such as river blindness, LF and loiasis are the cause of major public health and socioeconomic problems in Africa's co-endemic regions. River blindness is the second most common cause of infectious blindness in the world, while LF infects 120 million people across the globe and is the second leading cause of disability.

Writing in Science Translational Medicine, researchers said: "The device reported here provides an example of how mobile phone technology can be used to address critical gaps in the treatment of neglected tropical diseases."

Researchers hope the device could also be developed for use in detecting other infections.

Image courtesy of Prof Daniel Fletcher

The Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) is inviting applications from veterinary students to attend a one-week extramural studies (EMS) placement in July 2026.

The Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) is inviting applications from veterinary students to attend a one-week extramural studies (EMS) placement in July 2026.