The cables mesmerise the crabs and cause biological changes.

A study by Heriot-Watt University has discovered that underwater power cables for renewable energy sources mesmerise brown crabs and lead to biological changes which could affect migration habits.

Published in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, the study found that the cables for offshore renewable energy, which emit an electromagnetic field, attracts brown crabs and causes them to stay still.

The decreased movement means that the crabs are spending less time looking for a mate and foraging for food, as well as leading to changes in their sugar metabolism – storing more sugar and producing less lactate.

In a study of 60 brown crabs at the St Abbs marine station, higher levels of electromagnetism were found to cause cellular changes in the crabs, which affected their blood cells.

Alastair Lyndon, associate professor at Heriot-Watt University's centre for marine biology and diversity, told The Guardian: “Underwater cables emit an electromagnetic field. When it’s at a strength of 500 microteslas and above, which is about 5% of the strength of a fridge door magnet, the crabs seem to be attracted to it and just sit still.

“That’s not a problem in itself. But if they’re not moving, they’re not foraging for food or seeking a mate.

“The change in activity levels also leads to changes in sugar metabolism – they store more sugar and produce less lactate, just like humans.”

Kevin Scott, manager of the St Abbs facility, told The Guardian: “We found that exposure to higher levels of electromagnetic field strength changed the number of blood cells in the crabs’ bodies.

“This could have a range of consequences, like making them more susceptible to bacterial infection.”

Warning that this behaviour could have repercussions for the fishing industry, Lyndon told The Guardian: “Male brown crabs migrate up the east coast of Scotland. If miles of underwater cabling prove too difficult to resist, they’ll stay put.

“This could mean we have a buildup of male crabs in the south of Scotland, and a paucity of them in the north-east and islands, where they are incredibly important for fishermen’s livelihoods and local economies.”

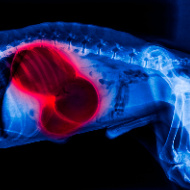

The Kennel Club is inviting dog owners to attend a free webinar on gastric dilation-volvulus syndrome, also known as bloat.

The Kennel Club is inviting dog owners to attend a free webinar on gastric dilation-volvulus syndrome, also known as bloat.